The Hidden Recesses and the Four Gates

Orçun Yazıcı

The Hidden Recesses and the Four Gates_September 2024

Orçun Yazıcı

September 2024

Ventilation building #1. Photo by Nick Somers.

I am an ant in the city of Antwerp

Curiously, impatiently, I walk through the narrow streets for hours, peering up at rows of brick facades with their small, medieval windows. I pause before a stone building adorned with crossed iron ties to prevent its collapse.

Amber.

Stepped gable.

The thin facade veils the realm inside.

What mysteries lie beyond this weathered wall?

A temptation swells within me to ring the doorbell and beg permission to peer inside. Could it be that this edifice is no mere building—but rather a gate to Antwerp’s hidden recesses?

I am an ant in the city of Antwerp

When the facade is merely a wall, I explore the realm beyond that wall

When the facade reaches out toward the horizon, I descend into earth, perpendicular

I am an ant in the city of Antwerp

Antwerp is my building and I trace the air shafts of this building,

To access the hidden recesses

Ventilation building #2. Photo by Nick Somers.

The facade struggles to be seen independently of the rest of the building, to be trusted on its own terms. We have relied on the facade to tell us stories about the politics and culture of societies; for instance, the extent of Baroque-era ornamentation signals the wealth and status of its patronage. But a facade, concealing what lies behind, highlights a dual nature: It is both curtain and mirror, joining the city’s fabric while keeping secrets to itself. Traces of vital infrastructure are glimpsed behind the mask, as with a ventilation building’s fixed expression covering the enormous air shafts positioned above underground tunnels, exchanging polluted air for fresh air in a continuous, heaving breath.

The facade is a hanging drapery of a theater set

Facade conceals, it is a mask

A facade is a dress: hinting, obscuring

Ventilation building #3. Photo by Nick Somers.

Ventilation building #4. Photo by Nick Somers.

Antwerp camouflages the new with the old, creating an impression of venerable antiquity and a seamless urban fabric. The city marks the hidden crossings of the River Scheldt with pairs of buildings facing one another across the water, standing above the underground tunnels that connect the left bank (Linkeroever) with the city center (Rechteroever). The famous Sint-Anna Tunnel, a prime destination for tourists, was built in the early 20th century for pedestrians and cyclists. Its entrances are located at two identical, standalone Art-Deco buildings (designed by Belgian architect Émile Van Averbeke in 1933) with facades clad in yellow brick. One is located in Sint-Jansvliet (Rechteroever), a lively public square shaded by large lush trees. This square serves as a basketball court during the week and transforms into an antique market on Sundays. The Linkeroever entrance, in contrast, is situated within a quieter residential neighborhood, distinct from the historic and bustling surroundings of the Rechteroever entrance. Beyond the ground level, these buildings are not shops nor apartments; they are vertical voids, disguised with a thin layer of facade to hide the residuals of modernity.

I embark on a journey into an unseen realm through a wood-framed glass door, where the antique musk mingles with the hum and rhythmic clatter of machinery. The gate opens and I enter one of the hidden recesses of Antwerp.

A short walk through a brightly glazed hallway leads me to the original wooden escalators, still in use after 90 years. I descend amid the mechanical thrum, and I’m walking through a tunnel, over half a kilometer long, clad in blue and white tiles.

The deeper I go, the stronger the scent gets.

Aged wood with hints of dampness.

At the end of the tunnel, this time I go up. There is a moment of deja-vu, but in reverse. The gate is closed now, time to leave the structure.

Ventilation building #5. Photo by Nick Somers.

Ventilation building #6. Photo by Nick Somers.

As I’m moving away from the gate, my imagination takes me to the 18th-century Potemkin village. The story goes that during an inspection trip by Empress Catherine II of Russia, Grigory Potemkin built fake facades all along the empress' route with the hope of impressing her—a village of illusion, rendering political and social prosperity through the facades.

My thoughts drift to the red tiled facades along Protocol Road, the airport road in Ankara, the capital of Turkey. The 15 km long highway is an important axis between the city and the airport, an introduction to Ankara that is intended to leave a lasting impression on local and foreign visitors alike. Red tiles clad the facade of every building along Protocol Road, but only the road-facing facade, to create an appealing and uniform street image. 300 years after the Potemkin myth, the facade is still trusted to convey a disguise, to create an illusion.

I soon find myself searching for traces of the hidden recesses in-between the buildings of Antwerp. One day during a visit, I stumble upon another Art-Deco building: one of the ventilation buildings of the Waasland Tunnel, which also crosses the River Scheldt. It is detached from the adjacent buildings, clad in familiar yellow brick and concrete Art-Deco elements.

I feel the coldness around the structure. My eyes travel along a long vertical window like a path to the sky, pausing occasionally on the concrete elements that disrupt its vertical continuity. Back on the ground, a dark small door crammed beneath the tower greets me like a gate to an unseen realm. I look across the river to Linkeroever and find a nearly identical ventilation building standing at the other end of the tunnel: structures not for the living, but for their mechanisms.

Ventilation buildings of Antwerp are gates to the hidden recesses:

Dark voids we created to fulfill our expectations from our environment.

As the demands of our cities grow, their infrastructural artifacts can no longer be discreetly tucked away in the corners of existing buildings; they insist upon their own accommodation within the urban fabric. The four gates of Antwerp, structures built to mediate the imposition of the mechanical behemoth into the urban realm nearly 100 years ago, invite reflection on the ethos of integration between the infrastructure of our cities and their human denizens.

First, the non-livings demanded space from the living;

then the gates of Antwerp appeared.

Ventilation building #7. Photo by Nick Somers.

Ventilation building #8. Photo by Nick Somers.

Orçun Yazıcı is a practicing architect based in Belgium.

Nick Somers is a freelance photographer based in Ghent, Belgium.

Seeing Things

Shantel Blakely

Decoding the Conversation_February 2024

Apollo and Daphne at Mestre

Shantel Blakely

February 2024

In the summer of 2022, I went to see the Splügen Brau warehouse in Mestre (in the mainland of Venice opposite the historic islands), one of several industrial buildings that often come up in an online search of the architect Angelo Mangiarotti. After a slow-moving journey along the back streets of Mestre, there I was. As I stood looking at the building, I was reminded of the myth of Apollo and Daphne and the eponymous sculpture by the Baroque sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini. As the story goes, Daphne was a forest nymph and a huntress who had chosen a celibate life. The god Eros, out of spite, caused his rival Apollo to fall in love with Daphne at first sight; Apollo gave chase. In flight, Daphne called for help. Her father, the river god Peneus, turned Daphne into a laurel tree. She survived, however encased and immobile. The transformation did not deter Apollo, who paid regular visits to Daphne, took the laurel as a personal emblem, and made this tree an evergreen whose leaves would not die. Bernini's Apollo and Daphne and Mangiarotti's Splügen Brau belong to different fields (sculpture and architecture) and different times and contexts (17th and 20th centuries), yet Bernini’s sculpture and the myth it represents provide terms through which to better understand what I saw—and just as importantly, did not see—as I faced Mangiarotti’s warehouse.

Photograph of the Splügen Brau warehouse. Giorgio Casali, Domus.

The Mangiarotti-designed warehouse sits by a canal that leads to the Venice archipelago. It was built for the beer company Splügen Brau, based a few hundred kilometers away, to provide a mainland depot where beverage cases destined for Venice could be transferred from trucks to boats. Like many of Mangiarotti's buildings, this design was a collaboration with another architect, Bruno Morassutti. The building owes much to a structural engineer as well: Aldo Favini. Its most expressive feature is a roof that hovers spectacularly above the canal. Building on his structural experimentation with prestressed concrete at Baranzate Church, Favini integrated construction method, load-bearing requirements, and architectural expression into a unified system.

Mangiarotti standing at the lower right corner of the photo, beneath the roof. Giorgio Casali, Domus.

What I was not able to see, standing by the warehouse, was the building in its original state—as I had come to know it in the photographs of Giorgio Casali. Casali was the in-house architectural photographer at Domus from 1951 to 1983 and documented the warehouse in detail in 1967. In Casali’s photos, one can see Favini’s interpretation of a trilith structure, its monumental system of beam and roof elements resting on eight slender columns (all of which sits atop a concrete plinth). Freed from structural necessity, the building’s enclosure is composed of (comparatively lightweight) corrugated, sliding metal panels. The roof overhang creates a shaded, sheltered space which extends farther out on the long axis than on the short one, and farthest of all on the canal end of the building. Seen from afar, the exposed ends of the roof system read like a slab resting on a series of beams. Casali’s close-up photos reveal a more sophisticated assemblage: Borrowing from the Hennebique method (devised to reinforce concrete against tensile forces), Favini conceived of the structure as a series of integrated, precast concrete components that could be craned into place.

Favini’s concrete structural component being craned into place. Giorgio Casali, Domus.

Details of the Hennebique method. Domus.

The resulting short-end elevation of each beam is a trapezoidal, jug-like shape, with the bottom of the beam wider than the top.

The symbolic nature of these elements, whose exposed ends read like caricaturesque representations of the beams themselves, underscores the analogy between Mangiarotti’s modern concrete building and architecture’s classical paradigm. (In classical architecture, elements like the triglyph are stone representations of the roof joists common in wood construction.) Casali’s photographs of the warehouse are also eerily reminiscent of depictions of the “primitive hut,” with its elemental structural system plainly visible.

Soane office, RA lecture drawing to illustrate the primitive hut: Perspective of a primitive hut, with flat roof, d: 20. May 1807. Sir John Soane's Museum Collection Online.

Daphne (”wrapped in thin smooth bark”; “her heart still beating” beneath it) came to mind when I considered how much of the detail revealed in Casali’s photos had become attenuated or muted in the building before me: Atop the original roof were added two additional layers, made of sheet metal and shallowly pitched; the plinth was boldly painted in yellow and white safety stripes; the enclosure was expanded to the edge of the porch on the canal side; and a new metal shed was built at the other end. These additions obscure the original design of the warehouse, but it continues to be used in the same way as when it was built. Certain features have remained, like the pale pink paint on the columns, now more faint than before, and the exposed, jug-like ends of the beams which are still visible along the roof's edge. With nothing more to go on than a distant view in an online navigation software, the features that remain visible or unchanged are what enabled me to identify (and find) the building in the first place. The timelessness of its elements blurs the distinction between function and decoration, allowing the building to remain and live in spirit—like Daphne, the nymph-become-tree.

Splügen Brau warehouse at Mestre. Photograph by author, July 2022.

If Daphne in the myth is symbolic of the building’s gradual encasement as described above, Bernini's rendition of the myth in sculpture reveals something else: When comparing Casali’s photos of Splügen Brau to the building in the flesh, it is immediately evident that the open space around the building has been lost. Casali’s images rely not only on the building for their impact and legibility, but also, like Bernini’s two-figured freestanding sculpture, on the availability of open space around it; the photographer’s own movement, as he shifts from one vantage point to another, is recorded in the photographs. The images reveal Casali’s use of open space as he walks a short distance away and peers up at the building, as he (probably) proceeds to walk farther away and turn back to shoot it again, and finally, as he crosses the canal and views it through fronds of grass. In his close-up shots, one can picture Casali standing on the building's plinth as he captures the connection between column and wall. Some of his close-up photos dissolve into patterns so abstract that they are hard to identify as one part or another.

Photograph of the Splügen Brau warehouse. Giorgio Casali, Domus.

Casali's photographs underscore the wealth of space Mangiarotti had at his disposal, and the role this played in the experience of the building; as if the architect anticipated and welcomed an ambulatory perceiving viewer, rewarding attention with gradually revealed information. In this respect the warehouse also has qualities in common with Baroque architecture (with its characteristic many-centered spaces exemplified in Bernini's own Sant'Andrea al Quirinale). Much like these distant works, Splügen Brau lends itself to being understood as a totality by way of the viewer's displacement in space.

In Bernini’s sculpture, details of the Apollo and Daphne myth are revealed as the viewer revolves around the object: Apollo is mid-stride, weight on his right foot; he has just reached Daphne and his left arm reaches forward and around her while Daphne, her feet elevated a few inches above the ground, is not quite running, nor standing. Daphne’s head is turned to the right and tilted back, her torso bent back while her arms reach up and forward. Bernini's frozen narrative allows a viewer to see the situation from Apollo's side, and—by moving around the work to the other side—from Daphne's. Apollo’s facial expression is calm, his gestures gentle, his limbs graceful. Daphne's forehead, too, has a youthful serenity, but as Apollo embraces her, the branches emerge from her hands, the roots shoot from her toes, the bark wraps her legs. Her downturned eyes show no sign of what is happening to her but the horror is there in her mouth, which prepares for a scream.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Apollo and Daphne. Photograph by author at Palazzo Borghese, Rome, June 2022.

As the spectator continues to revolve around the sculpture, a series of physical details are disclosed seemingly on a spiraling line, from Apollo’s right arm trailing gently behind him to Daphne's outstretched right arm reaching in front of her. Shards of bark around Daphne may serve as supports, but they are ingeniously part of the story as well, much more integrated and discreet than the stumps of wood that prop up many classical sculptures. There are no parts of Apollo and Daphne that the viewer is not meant to notice. Similarly on the Splügen Brau warehouse—as Casali captured it—each elevation has a distinctive face.

In the space around the Splügen Brau warehouse, fences cut the land into portions now filled by new buildings, including a factory in the field where Casali once regarded the depot from across the canal. At this point, one can neither view the warehouse from a distance nor walk around it. But just as the god paid tribute to the laurel tree, the owner keeps the building in use. The warehouse sits in a carapace of piecemeal additions that conceal its parts and mute its expressions just as the bark enclosed the nymph within a tree. Luckily for us, it still circulates as freely as ever in photographs.

Shantel Blakely is an architectural historian, architect, and educator. She is an Assistant Professor at the Rice University School of Architecture.

A Neighborhood Within

Mai Okimoto

Who Gets to Write?_January 2023

Re. Buildings

Mai Okimoto

January 2023

The ubiquitous low-rise office buildings that line Houston’s sprawling network of commercial corridors are a case study in an architecture of economic efficiency. Catering to diverse tenants, this typology has for decades offered flexibility and scalability—though often at the cost of overly sterile designs that say little about the tenants and their cultures. One is left with the impression that profit maximization inevitably locks this typology into the production of formulaic spaces with little formal variety, steering clear of untested or unnecessary spatial explorations.

Typical of Houston’s low-rise office buildings of this era, Corporate Plaza’s north and west façades are clad in mirrored glass. Less common are its east and south façades, which feature brutalist-like vertical bands that resemble pilasters.

7001 Corporate Drive in Houston’s Chinatown is a modest three-story office building that diverges from its typological cohort. At first glance, Corporate Plaza (built in 1980) does not appear to stand out from other buildings of the same typology. A closer inspection, however, reveals a calibration of density and scale that considers the tenants’ spatial needs, as well as moments shaped by feng shui, the traditional Chinese practice of arranging objects and space to be in harmony with their environment¹. Contrary to what one might infer from its name, Corporate Plaza is a conglomeration of tightly packed rental office units with a level of intimacy more common among apartment complexes.

Except for the pair of stone lions guarding the front entrance and the large red signage reading 華埠大厦 (”Chinatown Building”), the exterior of Corporate Plaza looks like a typical low-rise office or institutional building constructed in the second half of 20th century throughout the U.S.—the kind of unremarkable commercial remnant that one drives past without a second look. Yet past the lions, the building’s interior reveals another identity—one that resonates more closely with the sense of locality or community that comes through its other name: “Chinatown Building.” Its surprisingly compact scale and incorporation of oblique relationships are present from the entrance—the presence of a neighborhood further articulated by the display of disparate signages and artifacts of the tenants.

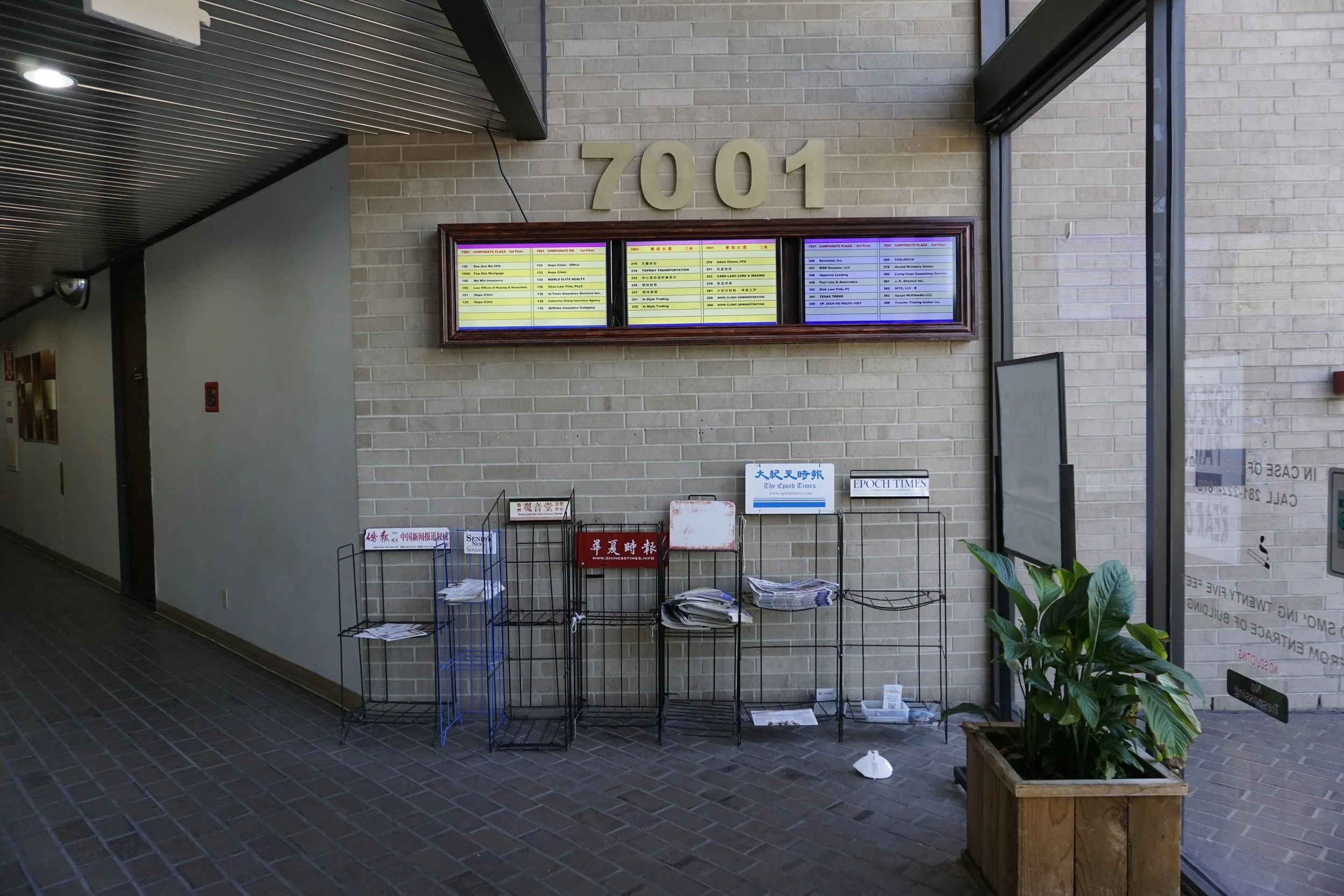

Within the vestibule, objects such as bilingual newspapers, tenant directory monitors, and a whiteboard for handwritten announcements bridge the building’s interior and exterior.

Behind the entrance doors, visitors step into a tall, narrow vestibule, where they are greeted by stands of Chinese and bilingual newspapers and a row of monitors displaying the tenant directory. With a slight turn (a move intended to dispel negative qi, which is thought to travel along straight lines) and a ceiling drop, the vestibule compresses into a dimly lit, narrow corridor. Cutting diagonally through the building and functioning as its spine, the corridor, connects the front and secondary entrances, and orients the building along its northeast-southwest axis. At the center of the diagonal spine is an atrium with a skylight, providing a natural light source into the building’s deep interior, as well as an opening for the qi to flow through the building.

The diagonal spine of the corridor expands into an atrium, which offers pockets of spaces partitioned by the circulation core and framed by greens.

The atrium, warmly lit through the skylight and fully enclosed on the upper levels by glazing on all four sides, feels small for an office building of this scale. Looking around, company names and phone numbers are laminated onto the windows here and there; the mix of English, Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean signs advertising law firms, travel agencies, and financial services offer glimpses of the buzz of activity taking place behind closed blinds. The garden and a running fountain—elements considered to bring prosperity and luck in feng shui—together with rows of mailboxes suggest an inner courtyard of an apartment complex, rather than an office atrium.

Compact office units form a dense mass around the open atrium, creating two contrasting spaces on the building’s upper levels.

At the atrium’s center are a pair of elevators enclosed in a decorated shell and a switchback staircase clad in white painted metal. The vertical circulation elements anchor catwalks that cross the atrium on the upper levels, echoing the diagonal spine running northeast to southwest on the ground floor. On the second level, the diagonal is carried from the building’s center to its periphery by the atrium catwalk, which transitions into a double-loaded corridor inside the mass of the building. The circulation diagonal is contained within a square; the double-loaded corridor makes a turn at the intersection to continue tracing the square offset from the building’s edge. Moving from center to periphery, the open and spacious atrium quickly disappears from sight. The identical doors of private offices appear one after the other on each side of the hallway and crowd the field of view.

Most of the rentable area consists of spaces ranging from 700 sq.ft. to 1,600 sq.ft. with the smallest leases starting at 300 sq.ft. While there are several larger suites, the interior parceling was likely designed with the businesses of recent immigrants in mind, often operating with a small workforce hailing from countries where population densities can exceed that of the U.S. by a factor of ten or more².

While private, the building is not anonymous, and has an atmosphere of a neighborhood or a community that is often observed in domestic spaces and smaller stores. In addition to elements that express the tenants’ presence, factors like the guiding design principles introduced by feng shui and the general disposition towards higher density and smaller scale have made Corporate Plaza into a low-rise office building that subverts typological expectations and is more than the capital returns of its real estate. It provides a space of community with a decidedly humane scale and composition.

Beyond its widely-popularized use in home interior decor, feng shui principles may be used to determine the orientation and configuration of buildings. Its practitioners seek to achieve a positive flow of qi, the Daoist concept of life energy, in order to invite good fortune and ward off bad luck.

One study indicates that per capita office space in Asia averages 100 sq.ft. compared to 140 sq.ft. in the Americas.