A Neighborhood Within

Re. Buildings

Mai Okimoto

January 2023

The ubiquitous low-rise office buildings that line Houston’s sprawling network of commercial corridors are a case study in an architecture of economic efficiency. Catering to diverse tenants, this typology has for decades offered flexibility and scalability—though often at the cost of overly sterile designs that say little about the tenants and their cultures. One is left with the impression that profit maximization inevitably locks this typology into the production of formulaic spaces with little formal variety, steering clear of untested or unnecessary spatial explorations.

Typical of Houston’s low-rise office buildings of this era, Corporate Plaza’s north and west façades are clad in mirrored glass. Less common are its east and south façades, which feature brutalist-like vertical bands that resemble pilasters.

7001 Corporate Drive in Houston’s Chinatown is a modest three-story office building that diverges from its typological cohort. At first glance, Corporate Plaza (built in 1980) does not appear to stand out from other buildings of the same typology. A closer inspection, however, reveals a calibration of density and scale that considers the tenants’ spatial needs, as well as moments shaped by feng shui, the traditional Chinese practice of arranging objects and space to be in harmony with their environment¹. Contrary to what one might infer from its name, Corporate Plaza is a conglomeration of tightly packed rental office units with a level of intimacy more common among apartment complexes.

Except for the pair of stone lions guarding the front entrance and the large red signage reading 華埠大厦 (”Chinatown Building”), the exterior of Corporate Plaza looks like a typical low-rise office or institutional building constructed in the second half of 20th century throughout the U.S.—the kind of unremarkable commercial remnant that one drives past without a second look. Yet past the lions, the building’s interior reveals another identity—one that resonates more closely with the sense of locality or community that comes through its other name: “Chinatown Building.” Its surprisingly compact scale and incorporation of oblique relationships are present from the entrance—the presence of a neighborhood further articulated by the display of disparate signages and artifacts of the tenants.

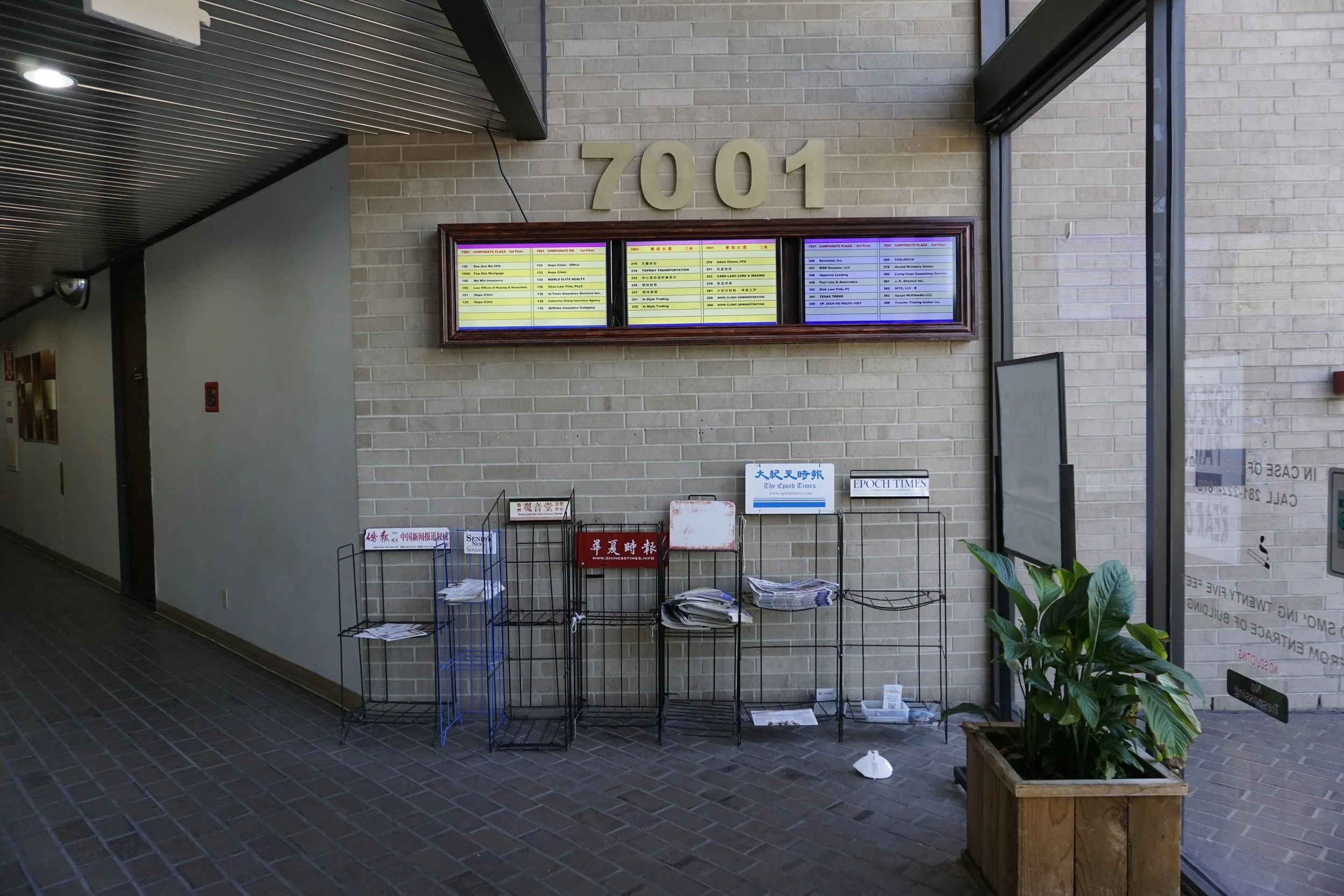

Within the vestibule, objects such as bilingual newspapers, tenant directory monitors, and a whiteboard for handwritten announcements bridge the building’s interior and exterior.

Behind the entrance doors, visitors step into a tall, narrow vestibule, where they are greeted by stands of Chinese and bilingual newspapers and a row of monitors displaying the tenant directory. With a slight turn (a move intended to dispel negative qi, which is thought to travel along straight lines) and a ceiling drop, the vestibule compresses into a dimly lit, narrow corridor. Cutting diagonally through the building and functioning as its spine, the corridor, connects the front and secondary entrances, and orients the building along its northeast-southwest axis. At the center of the diagonal spine is an atrium with a skylight, providing a natural light source into the building’s deep interior, as well as an opening for the qi to flow through the building.

The diagonal spine of the corridor expands into an atrium, which offers pockets of spaces partitioned by the circulation core and framed by greens.

The atrium, warmly lit through the skylight and fully enclosed on the upper levels by glazing on all four sides, feels small for an office building of this scale. Looking around, company names and phone numbers are laminated onto the windows here and there; the mix of English, Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean signs advertising law firms, travel agencies, and financial services offer glimpses of the buzz of activity taking place behind closed blinds. The garden and a running fountain—elements considered to bring prosperity and luck in feng shui—together with rows of mailboxes suggest an inner courtyard of an apartment complex, rather than an office atrium.

Compact office units form a dense mass around the open atrium, creating two contrasting spaces on the building’s upper levels.

At the atrium’s center are a pair of elevators enclosed in a decorated shell and a switchback staircase clad in white painted metal. The vertical circulation elements anchor catwalks that cross the atrium on the upper levels, echoing the diagonal spine running northeast to southwest on the ground floor. On the second level, the diagonal is carried from the building’s center to its periphery by the atrium catwalk, which transitions into a double-loaded corridor inside the mass of the building. The circulation diagonal is contained within a square; the double-loaded corridor makes a turn at the intersection to continue tracing the square offset from the building’s edge. Moving from center to periphery, the open and spacious atrium quickly disappears from sight. The identical doors of private offices appear one after the other on each side of the hallway and crowd the field of view.

Most of the rentable area consists of spaces ranging from 700 sq.ft. to 1,600 sq.ft. with the smallest leases starting at 300 sq.ft. While there are several larger suites, the interior parceling was likely designed with the businesses of recent immigrants in mind, often operating with a small workforce hailing from countries where population densities can exceed that of the U.S. by a factor of ten or more².

While private, the building is not anonymous, and has an atmosphere of a neighborhood or a community that is often observed in domestic spaces and smaller stores. In addition to elements that express the tenants’ presence, factors like the guiding design principles introduced by feng shui and the general disposition towards higher density and smaller scale have made Corporate Plaza into a low-rise office building that subverts typological expectations and is more than the capital returns of its real estate. It provides a space of community with a decidedly humane scale and composition.

Beyond its widely-popularized use in home interior decor, feng shui principles may be used to determine the orientation and configuration of buildings. Its practitioners seek to achieve a positive flow of qi, the Daoist concept of life energy, in order to invite good fortune and ward off bad luck.

One study indicates that per capita office space in Asia averages 100 sq.ft. compared to 140 sq.ft. in the Americas.